For a century, Mirror Pond has been a focal point of Bend and the backdrop to images of the city.

It isn’t a natural part of the city. Mirror Pond is man-made, formed in 1913 with the construction of a hydroelectric dam near the Newport Avenue bridge.

And the slow water flowing by Drake Park comes with problems — sediments and aquatic plants have built up behind the dam, leaving smelly muck exposed when the river is low.

The pond was dredged in 1984, and this winter a group of local government and business representatives decided to hire a consultant to lead an effort to examine ways to clean up Mirror Pond in the future. No one has yet determined what those alternatives will be, but the plan is to encompass a range of ideas.

One option could be to remove the dam and turn Mirror Pond back into a free-flowing section of the Deschutes River.

“When we look at a project like Mirror Pond, we really try to put all of the crazy ideas on the table,” said Ryan Houston, executive director of the Upper Deschutes Watershed Council. “Everything from removing the dam, at one end of the spectrum, to doing nothing and sitting on our hands. And (we) try to ask all the questions — what would happen?”

No one knows for sure what the river flowing by Drake Park would look like if the hydroelectric dam was torn down. The dam itself generates enough power for about 800 homes, and removing it could upend existing ecosystems, upset adjacent property owners or move sedimentation problems downstream, according to some involved with the Mirror Pond issue.

But returning the pond to a river could also present opportunities to create new wildlife habitat or park space, and allow for a more natural river through downtown Bend.

“Mirror Pond has kind of been an icon of Bend ever since it was built,” said Don Horton, executive director of the Bend Park & Recreation District. “And it would really change the character of Drake Park and the downtown area if it was to be more free-flowing.”

The park district, along with the city of Bend, William Smith Properties and Pacific Power, which operates the hydroelectric dam, have hired Michael McLandress, of Brightwater Collaborative LLC, to look for funding and subcontractors to examine possible solutions for Mirror Pond.

Removing the dam is an option that the analysis will probably address, along with the effects of doing nothing, Horton said.

But the most realistic option is somewhere in the middle, he said.

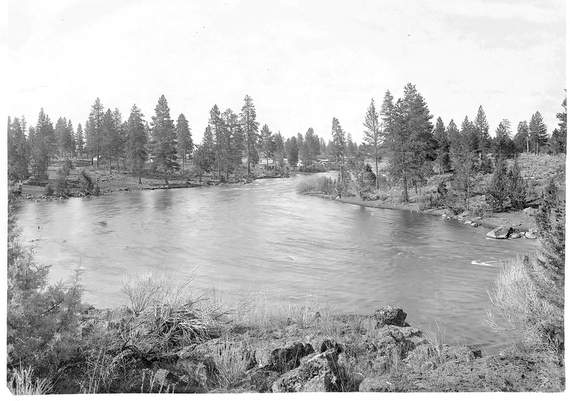

If the hydropower dam was removed, one way to gauge what Mirror Pond would look like is to dig up photos taken before the dam was installed, Houston said.

“Really what it shows is that that’s a fairly gentle section of river,” he said. “The slope is not too steep, and the water’s not moving too fast.”

Without the step currently created by the dam, the river would smooth out its slope along the stretch between the Colorado Avenue Dam and the dam downstream by Portland Avenue, he said.

It’s not that big of a drop, he said, so there probably wouldn’t be fast water like at the First Street Rapids, Houston said. Instead, Mirror Pond would probably look more like the section of river that flows under the Bill Healy Bridge on the south end of Bend.

Currently, Mirror Pond creates a bulge in the Deschutes River as it goes through Bend, he said. Without the dam, that would narrow out in parts, probably by about 40 percent in some sections.

“As the water moves through more quickly, the channel is getting narrower and perhaps deeper,” Houston said.

A narrower river channel would expose big mudflats, he said — but that could just be temporary.

“This is where it takes some imagination and some landscape restoration planning,” he said.

There’s a gooey layer of muck currently lining Mirror Pond, he said. And if a new, narrow route for the Deschutes River is created, some of that would be exposed, and probably would have to be removed. After that, restoration workers could create wetlands, riparian habitat, extend the grass of Drake Park, or put in a boardwalk or dock for kayaks and canoes — whatever the community decided to do, Houston said.

The watershed council isn’t proposing any one solution to the problem of sediment building up in Mirror Pond, Houston said, noting that it’s a complicated issue as well as one that’s sensitive politically, economically and ecologically.

“No matter what we propose, there’d be a whole series of trade-offs, good and bad,” he said.

Matt Shinderman, senior instructor of natural resources at Oregon State University-Cascades Campus, said that as an angler, he’d be thrilled to see a river flowing by Drake Park. People could take their kids to the park to fish, he said. But others also enjoy the still, pond-like atmosphere of Mirror Pond.

One potential problem with removing the dam, Shinderman said, is that it could simply flush the sediments — and the water- quality issues that go with sedimentation — to an irrigation diversion dam near The Riverhouse.

“It would just shift the problem downstream,” Shinderman said.

And although the dam is a man-made object, the ecosystem above and below it has adapted over the last century, he said. A free-flowing river would alter existing currents, pools and other wildlife habitat, he said, possibly displacing populations of insects, fish and birds — although others could adapt in the future.

“When you remove dams that have been in place for a long time, you often don’t get what you thought you were going to get,” he said.

Another potential issue is the dam itself.

The 14-foot-high hydroelectric dam at Newport Avenue was built in 1913, and has been operated by Pacific Power or its predecessor companies since 1930, said Tom Gauntt, spokesman with Pacific Power. It creates a mile-long, shallow reservoir behind it, he said.

And the water that flows through it creates about 1.1 megawatts of power — enough to supply electricity to about 800 typical houses.

Removing the dam is “very hypothetical,” he said, and there is no existing proposal to do so.

The company has removed dams before, he said, including the Powerdale Dam on Hood River. That dam was a little larger than the Newport Avenue Dam, he said, and was also in an isolated canyon — not right in the middle of a populated area. It cost more than $3 million to remove the dam, he said, noting that costs vary for different projects.

Removing a dam takes a lot of time, he said — one project has been ongoing for more than a decade — as well as agreement between multiple federal, state, local and tribal entities.

“There’s many, many parties when something’s been part of a community for 100 years,” he said. “Even if everyone agrees, it’s a lengthy process.”

And some people, including some who live along Mirror Pond, are adamantly opposed to removing the dam.

“I’d absolutely go crazy. Mirror Pond is Bend,” said Charliene Wackerbarth, who has lived along Mirror Pond for almost 20 years. “That’s the signature and, to me, the most important part.”

People float down to the pond in the summer, or canoe and kayak in it, she said, while families picnic along the pond’s edge.

Changing the pond into a river might make her lawn bigger, since their property extends to the middle of the river, but Wackerbarth said that’s not worth it.

“I personally would fight this,” she said, adding that she would prefer an option that involves dredging the sediments. “Keep it as this gorgeous, wonderful lake.”

Thomas Ackerman said his opinion may be biased, because he lives along Mirror Pond, but said he wouldn’t want to see it changed to a river.

“I think it’s a total jewel for the city, and to see it gone would be really sad,” Ackerman said. “It’s so beautiful, I feel like it was meant to be that way even though it is a man-made pond.”

Creating mudflats by switching from a pond to a narrow river could draw in more mosquitoes, he said, and he wondered whether people would have to drag canoes through the silt to get to the river.

“I love going out there on a canoe and paddling around,” he said. “Even though it’s shallow, it feels like a big body of water that you’re out on.”

It’s hard to estimate what effect removing the dam might have on property values along Mirror Pond, said Steve Scott, principle broker with Steve Scott Realtors in Bend.

If residents kept their ownership of the land up to the river’s edge, it might not affect property values too much, he said. But if the land between the old Mirror Pond high-water mark and the new Deschutes River high-water mark was turned into public land, and people lost their direct waterfront property, that would greatly decrease the value, Scott said.

Along Mirror Pond, some people do own the land out to the river’s center line, said Aaron Henson, senior planner with the city of Bend.

The properties along the river are subject to the city’s waterway overlay zone. One part of the overlay zone states that along the riparian corridor, the city reviews any kind of development applications to make sure the projects won’t disturb wildlife habitat and vegetation.

By Mirror Pond, that corridor is 30 feet from the ordinary high- water mark, he said — and if Mirror Pond narrows to a free-flowing river, that corridor could shift as well, unless the city changes the zoning language.

Along the Deschutes River, there are also setback requirements that range from 40 to 100 feet, he said, as well as requirements about the types of building materials that people can use. Those could be shifted with a new ordinary high- water mark as well.

There will be community meetings and outreach in the future to discuss the different alternatives for Mirror Pond, said McLandress, who is working on hiring a subcontractor to examine different options. And until that analysis of options is done, it’s hard to say what Mirror Pond would look like under different conditions.

But no matter what happens to Mirror Pond, beer-lovers don’t have to worry about the brew that bears its name.

Mirror Pond Pale Ale is Deschutes Brewery’s No. 1 selling beer, said Jason Randles, digital marketing manager with the Bend brewery. It’s sold in 16 states and one province.

“Most people (who drink Mirror Pond) have never been to Bend. The brand, and the beer, lives beyond the actual place,” he said. “We’ll just keep making the beer.”